The 442,000-square-foot, unnamed property will be located at 1015 SW 1st Ave. and feature high-end amenities and 2,000 square feet of ground-floor retail space.

Posts

One Brickell City Centre would soar about 1,000 feet high. Currently, the tallest building in both Miami and Florida is Panorama Tower at 868 feet.

Brickell City Centre won the initial green light to expand its footprint, creating two new mixed-use towers within a more than 100,000-square-foot annex to the $1.05 billion project.

The Miami City Commission just approved on first reading an amendment to Brickell City Centre’s special area plan that adds 15 properties owned by Colombian businessman Carlos Mattos, who is partnering with Brickell City Centre developer Swire Properties on the 104,287-square-foot expansion.

According to documents submitted to the city, Mattos and Swire want to build a 54-story building that would have 588 residential units, 84,009 square feet of commercial space and 832 parking spaces, as well as a 62-story tower with 384 residential units, 3,275 square feet of commercial space and 399 parking spaces. Among the sites is the former home of Tobacco Road, the famed watering hole that lasted 102 years before a wrecking ball claimed it in 2014.

Akerman attorney Neisen Kasdin, who represents Swire, told city commissioners the project will likely not break ground until the next cycle.

“It is market-dependent of course because there will be for-sale units there,” Kasdin said. “We are probably looking at a two-to-three-year period.”

The proposed Brickell City Centre annex would also have 11,718 square feet of civic space and the joint venture partners have agreed to build a connection to the Miami Riverwalk, add lighting to the South Miami Avenue Bridge. They will also donate $1 million to the city to be used for renovating single-family houses owned by low-income individuals.

The 15 properties run between Southwest 5th and 7th streets along South Miami Avenue and total just over 2 acres. In 2012, Mattos’ Tobacco Road Property Holdings LLC paid a combined $15.44 million for the majority of the assemblage which consists of nine adjacent properties at 11, 21, 31, 37, 45 and 55 Southwest Seventh Street and 622, 626 and 640 South Miami Avenue in 2012. Swire affiliate BCC Road Improvement LLC paid $4.7 million for the roughly 15,000-square-foot corner piece at 602 South Miami Avenue in 2014.

The expansion still requires final approval, which is often likely once it has been approved on first reading. Brickell City Centre’s first phase included two 390-unit condo towers, Reach and Rise; a 500,000-square-foot outdoor mall; an office building and a 40-story hotel, East, Miami.

Source: The Real Deal

For decades, these three large city blocks in a prime location — straddling Miami Avenue and butting up against the Miami River and the Brickell financial district — lay inexplicably vacant.

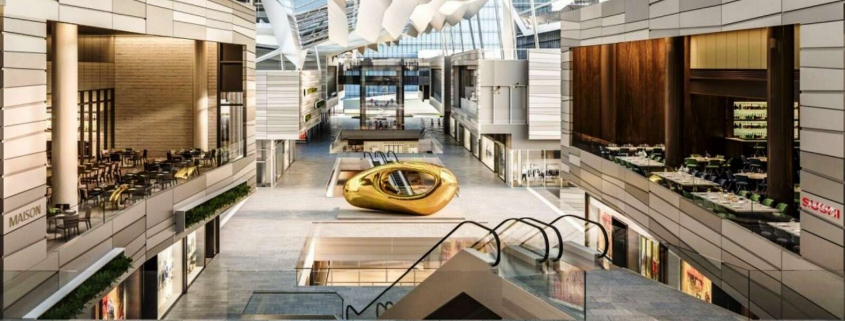

Now, in the seeming twinkling of an eye, they have been utterly transformed. Brickell City Centre, which opened in November, is an urban animal of a concentrated intensity more evocative of Hong Kong or Tokyo than anything Miami has seen before: five towers connected by a multi-level, open-air shopping center plugged directly into a Metromover station and layered over underground parking tunneled beneath the streets. Pedestrians enter porous breezeways seamlessly from the surrounding streets, while above, shoppers cross bustling pedestrian fly-overs, protected overhead by a “climate ribbon” canopy that snakes across all three blocks like a long strip of origami.

It feels like a real city. And that’s precisely the stated goal of the relatively new, largely untested and increasingly controversial zoning category that produced it, and that now may be paving the way to a redrawing of broad swaths of Miami.

The goal: to create true urban neighborhoods and districts in underdeveloped areas of the city that, far from being self-contained islands, are painstakingly planned, interwoven and compatible with the city fabric around them. Often in exchange for greater height and density, developers must spend millions on new public spaces, streets and amenities — sometimes paying cash into public kitties — while giving city planners and the city commission a significant say in the shape of the final product.

The concept has taken off, to the consternation of some neighborhood activists. SAP was once reserved mostly to the city’s core, but developers building in far-flung, residential neighborhoods are now taking advantage.

“What the SAP does uniquely is, it sets up a table where the city comes in, stakeholders come in, and we can all figure out what the optimal shape this project can take is,” Miami planning director Francisco Garcia, who helped author the Miami 21 code while at the private planning firm Duany Plater-Zyberk, said in an interview. “In Miami, I don’t think there is any area that is not undergoing some degree of change, or redevelopment, or thinking about redevelopment. This is our world today here in Miami. So let’s approach this emphasis to redevelop and reshape the city in a creative way, and have it yield the best results.”

Aside from Brickell City Centre, which has two more planned phases yet to start, the SAP has also led to the lauded, near-total redevelopment of the formerly dormant Miami Design District. The rebirth of the district, about 60 percent complete, has meant new, street-friendly retail buildings and a pedestrian promenade connecting two large public plazas.

Aside from Brickell City Centre, which has two more planned phases yet to start, the SAP has also led to the lauded, near-total redevelopment of the formerly dormant Miami Design District. The rebirth of the district, about 60 percent complete, has meant new, street-friendly retail buildings and a pedestrian promenade connecting two large public plazas.

Meanwhile, on the north bank of the Miami River, River Landing would bring a multi-story restaurant and retail center with apartments to the site of the demolished Mahi Shrine in the Civic Center area. On the south bank, Chetrit Group’s $1 billion Miami River complex would bring 58- and 60-story towers and three levels of shops to a site formerly occupied by an abandoned restaurant and empty warehouses. Both projects would include new public spaces; Chetrit would underwrite upgrades to Jose Marti Park and contribute millions into an affordable housing trust fund.

If anything, these projects were celebrated. But as SAP applications proliferate across the city for everything from tech villages to mixed-use residential and commercial districts and even school and hospital redesigns, the sheer size and scale of some of the proposals is giving many city residents pause, if not provoking outright alarm.

Entrepreneur Moishe Mana’s massive Mana Wynwood SAP, which would bring shops, a trade center and residential towers rising up to 24 stories to two dozen acres of mostly vacant land, prompted a year of negotiation and public battles with other property owners in the rapidly redeveloping warehouse district. Mana won commission approval after agreeing to spend millions putting utilities under ground and redrawing the original plan to scale back construction facing the heart of Wynwood.

Elsewhere, developer Michael Simkins talked about using the SAP process to design an innovation center in blighted Park West immediately south of Interstate 395, including a controversial observation tower designed to also serve as a digital billboard, although his attorney says he’s currently reassessing whether to pursue an SAP.

And now a flurry of potential new SAPs has raised concerns that the process could become a runaway train barreling through established neighborhoods and dramatically changing their character. In and around the city’s Upper Eastside, three developers and a hospital have submitted applications to the city or are expected to soon, all within a tiny area of roughly 40 square blocks:

- Legions West, a 1.2-million-square-foot complex abutting Legion Park, to be built on the site of a recently demolished American Legion post and neighboring Art Deco apartment buildings that formerly housed dozens of low-income families. The developer would spend millions on improvements to the park.

- Eastside Ridge, proposed by the owners of Design Place, who want to turn 22 acres of moderately priced townhouse units into a mass of sky-high residential and office towers with nearly 3,000 condos.

- Miami Jewish Health Systems, across Second Avenue from Design Place, which is planning an expansion of an existing campus. The hospital wants to open a new dementia-focused assisted living facility, research center and convention hotel, and redesign other aspects of its campus.

- Magic City, a 15-acre assemblage including industrial buildings and a demolished trailer park straddling Little Haiti and Little River that developers Tony Cho and Bob Zangrillo want to convert into a technology, residential and cultural center.

Legions West and Eastside Ridge are perhaps the most controversial of the SAP submissions to date, in part because they would tower over neighbors and replace low-rise, low-cost rental housing. The Legions project would drop four towers up to 15 stories tall next to two protected historic districts: the MiMo Biscayne district with a 35-foot height limit, and the single-family Bayside Historic District. It would also include part of the adjacent and now-historic Legion Park in order to qualify for the needed nine acres to propose an SAP — an aspect that generated false fears that the developer, who plans to spend millions on upgrades, would privatize the park.

Renderings of the Eastside Ridge plan, which depict what seems to be a massive, gleaming steel-and-glass city-within-a city rising from the modest urban landscape of Little Haiti, has sent residents into a tizzy. Some in the community, already hyper-acute to the pressures of gentrification, believe they are being boxed in and pushed out by new development.

“The more we learn about these mammoth projects, the more concerned we are,” said Marleine Bastien, a Haitian-American activist who has been outspoken about gentrification of the neighborhood and the apparent lack of consideration for community input. “What we resent is for us to be brought in at the 11th hour when everything is cooked and ready to eat, and we get the crumbs.”

Garcia, Miami’s planning director, insists that community input is a central tenet of the Special Area Plan, which requires reams of paperwork, months of debate with city planners and multiple hearings in order to green-light a project. But some critics say there is evidence to the contrary.

“In Wynwood, they up-zoned 45 different properties to as high as 20 and 24 stories, which is a complete violation of the law,” said veteran Morningside activist Elvis Cruz, who argues that the city is flouting a Miami 21 requirement that all new development be compatible with its setting. “But that’s the way it works in the city. They just interpret things as they wish. It’s completely out of scale and character.”

People critical or skeptical of some of the newer SAPs even includes some prominent figures who have strongly backed such projects in the past. Horacio Stuart Aguirre, chairman of the Miami River Commission, which reviews projects along the waterway, said it’s one thing to approve SAPs on undeveloped land long contemplated for dense redevelopment, like the river properties close to downtown Miami, but entirely another to plunk those down amid settled, existing neighborhoods.

Though SAPs must be approved by the city commission, which has been no rubber stamp, Aguirre says he fears the “goodies” promised by developers of SAPs to the city — including new jobs, the creation of new public spaces and payments toward future affordable housing — prove too tempting to turn down. (None has been, yet.)

“Brickell City Centre is a wonderful idea, where it was done. It’s in Brickell, for crying out loud,” Aguirre said. “But should we have 20 of those reiterations all over the city? What happens to the character of individual neighborhoods? What happens to the idea of local communities?”

But Miami 21 designers say the SAP has always encouraged developers to embrace the neighborhoods in which they’re investing, and put in the extra expense, effort and time that sensitive master planning requires. They note that developers, even without SAPs, could always pursue up-zoning without providing anything in return to the community.

“They are a terrific improvement over the prior situation,” said Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, whose firm authored the Miami 21 code. “It’s an invitation to making a better plan than what is there now.”

Garcia also says the city puts SAP proposals through a grind of an extensive review, and some submissions never make it out of the process because developers drop them after realizing what’s required for approval. He disputes the idea that developers and the city use SAPs in order to super-size projects.

“The perception by some is this is simply a race for the gluttonous,” Garcia said. “But I will tell you there are significant amounts of development capacity and density that are left on the table in each and every one of these SAPs.”

To be sure, height and density are part of the equation, but not the entire picture. What makes SAPs attractive to the city and developers is the flexibility afforded in designing what often are sprawling campuses. Roads can be moved. Buildings can be massed and shifted in ways they otherwise couldn’t. The rigidities of the city’s laws can be unlocked, although not ignored. “If I have the possibility to do that, why wouldn’t I?” asks Garcia.

Noting that the Design District SAP is hardly tall by Miami standards, Magic City’s Cho said he expects to submit an application for an SAP in part because the project he wants to build — the one he says is best for the area — is impermissible under the regular zoning code. For one thing, much of the 15 acres he and Zangrillo own are zoned industrial, and Cho says he’s hoping to include hundreds of low-cost residential units. Likely, that will be done by building “micro” units, tiny apartments made affordable by their size.

“The existing zoning is antiquated and outdated,” said Cho, who began investing years ago in Little Haiti real estate. “That’s not in the best interest of Miami. You don’t want a neighborhood that can’t develop residential.”

For Garcia, whose department hasn’t weighed in on Magic City, and has only begun to look at Eastside Ridge and Legions West, that’s the underlying truth behind Miami’s transformation. The city is evolving, and as downtown and Brickell become entirely built-out, and Wynwood’s land becomes price-prohibitive, developers will begin to invest and rebuild the city’s farther-flung neighborhoods. When that happens, he says, the city needs the tools to map out the right future.

“There has been a great explosion of building in Miami during the last six or seven years. But that’s a data-point. The real question is: Is that good? Is that bad?” he says. “It is a very positive trend and it is getting us closer to what Miami is and should be. Miami will not be in the near future a sleepy town that is a vacation resort for the wealthy. It should be a real city.”

Source: Miami Herald

The commercial real estate market outlook for Miami-Dade: Sunny, as long as more mass transit is on the horizon, said industry experts at the Building Owners and Managers Association of Miami-Dade’s 2017 Commercial Real Estate Outlook event.

In the office market, rents are at an all-time high in certain sub-markets, said Brian Gale, Cushman & Wakefield’s vice chairman of Brokerage Services who represents nearly 5 million square feet of office space in South Florida.

On Brickell, office space is hitting around $60 a square foot for Class A space; back in 2008 the high was in the upper $40s, said Gale, during the panel discussion at the East Miami in Brickell. Downtown Miami is just behind it, and Aventura and Airport West have also hit all-time highs, too, he said. Coral Gables presents a different story, he said. In 2007-08, rent in the trophy buildings was $46-$48 a square foot; today it’s the low $40s.

“For many years, Coral Gables was the darling of the office market. I would say it has a temporary black eye with less demand and blocks of spaces still existing. But Coral Gables also has the most to gain,” Gale said.

Gale sees the South Miami market as vaulting too, once new mass transit options fully kick in for the area.

“The traffic on Useless 1 is not getting any better. … Miami Beach needs to figure out a way to get light rail over there.” Gale said. “Rental rates will continue to increase in 2017. Looking further out, being a gateway city … there is no reason to believe we couldn’t be a $70 rental market in 2022.”

Growth in shared office spaces has exploded — for instance, WeWork recently leased 65,000 feet at Brickell City Centre and there are now more than 20 shared workspace centers in downtown Miami alone. Sometimes these shared office centers can act as an incubator for a building; when the companies grow out of the co-working space they take space on other floors, Gale said. In the broader office market, expect more smaller offices, with more open spaces and cubicle areas on the outside of the floor with the glass-walled offices in the center, he added.

In the industrial sector, with job growth projected to slow in 2017 and 2018, is that a concern with 1.8 million square feet coming online in 2017 and 1.4 million in 2018?

“That’s actually less than half of what we have seen in 2015 and 2016.” said JLL Managing Director Brian Smith, who led the team representing NBC Universal/Telemundo Enterprises in the record breaking lease of over 550,000 square feet for a world headquarters broadcast center in western Miami-Dade.

He said he looks more closely at population growth. In both the office and industrial markets, new-to-market tenants are pushing the records. The last three years have brought more than 700,000 square feet of new-to-market office tenants. But that’s more than the previous 15 years combined, Gale said.

The last two years saw 300,00 square feet of new-to-market industrial tenants, but this year it will be 2 million and perhaps 3 million square feet.

“John Deere, new names. We have quickly become one of the most important industrial markets on the globe,” said Smith. “Three large deals in the works may be the biggest ever, in addition to the NBCUniversal deal.”

To be sure, urbanization has transformed the retail landscape, with Miami’s downtown population now approaching 90,0000 people, a 30 percent increase since 2010, with an incredibly affluent demographic, said David Moret, president of Highline Real Estate Capital, which acquires and redevelops office and retail properties with capital partners.

Retail rents are in the stratosphere on Lincoln Road, surpassing $300 a square foot. They are hitting $200 in the Design District and Coconut Grove and Wynwood are flirting with $100 a foot, Moret said. How far will they go?

“I think we have gotten ahead of ourselves,” Moret said. “ I think there will be a reset. … We are already seeing resistance. We are seeing leasing volume way down on Lincoln Road.”

He sees the biggest impact coming from millennials, a group that will have the most spending power by 2017. This means tenant mix is more important than ever.

“Successful centers are going to be about creating experiences, to give people a reason to go there instead of click on their phone,” said Moret.

Source: Miami Herald

About 2.3 million square feet of retail space is set to deliver in Miami by 2018. What will a massive influx of retail supply mean for the overall market?

Jason Shapiro, managing director at Aztec Group, has some opinions. First, he tells GlobeSt.com, it’s noteworthy that the vast majority of that space—approximately 1.4 million square feet—is located within Brickell and Downtown Miami with major mixed-use projects such as Brickell City Centre, Miami Worldcenter and Met Square fueling this new development. That’s according to a Miami Downtown Development Authority.

“While the delivery of over 2 million square feet of retail space by 2018 may sound like a huge number, it is not necessarily an oversupply,” Shapiro says. “Historically speaking, the Miami’s Central Business District has been underserved in terms of access to high quality, international retail brands.”

As Shapiro sees it, substantial residential growth in the Downtown Miami area, along with organic employment growth and increased visitation, have all contributed to improved retail fundamentals. The DDA report found that over 30% of tourists to Miami in 2014 visited the downtown area. That’s a record-breaking number.

“As our city’s demographics evolve and neighborhoods such as Downtown Miami and Wynwood continue to build up and grow more sophisticated, the stronger market fundamentals support the fact that the additional supply will meet demand,” Shapiro says. “Most of the new product coming down the pipeline is luxury, high-street retail that will serve new demographics that live and work in those key urban areas.”

Source: GlobeSt.

Slower sales and a glut of inventory has led to a buyers’ market for South Florida luxury properties, according to Miami Beach real estate agent Jill Eber.

“For almost five years we were just on an upward spiral,” Eber, of Coldwell Banker’s the Jills, told a gathering of real estate professionals Wednesday evening. “But, right now, it has adjusted and it has become more of a buyers’ market. As a result, developers are adjusting their pricing and increasing broker commissions to move units. In no way is this like 2008, 2009, and 2010. The market has been steady.”

Eber participated on a panel hosted by the Miami chapter of the Asian Real Estate Association of America at Brickell City Centre’s East, Miami hotel. The discussion was moderated by Coldwell Banker luxury real estate Vice President Craig Hogan and featured Debora Overholt, Brickell City Centre’s vice-president for retail, Swire Properties Vice President Maile Aguila, Eber, Miami Association of Realtors President Teresa Kinney and Ramona Messore, vice-president of Saks Fifth Avenue at Brickell City Centre.

Overholt and Aguila offered their insights into Swire’s ability to finish massive developments like Brickell City Centre. Overholt noted that the $1 billion nine-acre mixed use project is modeled after Pacific Place, a complex of office towers, hotels and a shopping centre the company built in Hong Kong 27 years ago.

“If you are familiar with Pacific Place, what we are developing is very similar to that,” Overholt said. “We are very excited to bring something fairly new to U.S. retailers, but something we already do well.”

Since opening in 1989, the four-floor mall at Pacific Place has more than 711,000-square-feet of retail space that houses a Harvey Nichols department store and 140 luxury brand shops and boutiques. Similar to Brickell City Centre, the mall is integrated into three Class A office towers, four five-star hotels, and a condominium. Swire spent $2.1 billion in 2011 on a redesign project led by Thomas Heatherwick.

Aguila told the audience Swire’s success with Pacific Place proves the company has the strength and wherewithal to deliver every phase of Brickell City Centre.

“When we do things, we do things long-range and take a long time,” Aguila said. “I remember when we were developing Brickell Key, we were all looking forward to a retail component and food and beverage component that just never happened. We saw that need. We had the vision to come into the area at the right time and the right place.”

Source: The Real Deal

As talk of the softening condo market buzzes through South Florida, a massive project in Miami’s urban core is unfolding.

As it debuts — and on schedule, no less — Brickell City Centre, a mixed-use complex of luxury condo towers, class-A office buildings, a five-star hotel, and a sprawling open-air shopping center featuring Saks Fifth Avenue, is expected to transform Brickell’s business district from a banking ghetto to a true live, work, shop and dine nexus.

The 5.4 million-square-foot development is designed to elevate the downtown Miami pedestrian experience and breathe new life into the neighborhood. With Swire Group’s track record of successful development on Miami’s Brickell Key and in the parent company’s home city of Hong Kong, the odds are in its favor.

“This destination is — and I don’t wanna overuse the word — pivotal, and a catalyst,” said Alyce Robertson, executive director of the Miami Downtown Development Authority.

The project’s caliber and scale have raised property values west of the waterfront. Surrounding developments have even taken to marketing their own projects around City Centre, calling it a neighborhood amenity.

Already built are two elements key to access: a Metromover station refreshed by Swire and integrated into the project, and underground parking stretching across five continuous city blocks, with entrances facing major arteries.

Reach condo residence with an east-facing view at Brickell City Centre, a 9.1-acre mixed-use project in downtown Miami (PHOTO CREDIT: CHARLES TRAINOR JR.)

Recently opened is one of two condo towers, the 390-unit Reach. The second 390-unit tower, Rise, is expected to be completed this summer. Also completed is the 130,000-square-foot Class A office building. The 352-room upscale hotel, EAST, Miami is slated to open May 31. The first shops in the 500,000-square-foot multilevel retail area — including Saks Fifth Avenue — are slated to open in the fall. A timeline has not yet been set for an 80-story third tower expected to be the tallest building in the southeast.

All were designed by Miami’s Arquitectonica. Plans for the site’s northeast corner have not yet been disclosed.

Unifying the sprawling complex is its platform design, set above the city that allows pedestrians to stroll from one building to the next without crossing the street. And above it all is a first-in-the-world climate ribbon, a passive cooling system that offers shade, collects rainwater and doubles as an eye-catching attraction.

Impact

The development will create more than 6,000 local jobs, bringing a boost to Miami’s hospitality and retail sectors.

For Swire Group and its local subsidiary, Swire Properties, Brickell City Centre represents a long-term investment of more than $1 billion in a project whose value will continue to accrue for decades. In 2008, when hints of the megaproject first emerged, the U.S. economy looked bleak.

“The market was disastrous. Wall Street collapsing. The housing market nationwide collapsing. And we were the poster child for failed condos,” said Ezra Katz, CEO of Aztec Group, a real estate investment firm.

More than 30,000 condos throughout downtown Miami were empty. Developers across the area began to offer units in bulk at deeply discounted prices. Experts predicted it would take as many as 10 years for the market to bounce back. Development halted. Some projects went into foreclosure.

“It created a Depression-like atmosphere in Miami. I looked at every aspect of the market and it all looked dark to me,” Katz said.

Swire’s bold purchase of 5.65 acres represented a welcome vote of confidence in a struggling city.

“We were in the worst recession the country had seen, but we believed in Miami,” said Steve Owens, president of Swire Properties.

The deep-pocketed company was able to invest without bank loans or public subsidies. Elsewhere, the publicly traded company — whose holdings include Cathay Pacific Airlines and Swire Hotels — boasts a portfolio of mixed-use developments, including Pacific Place in Hong Kong and INDIGO in Beijing, and operates a massive trade division that dabbles in industries as varied as cars and footwear.

The timing of its investment, while risky, proved fortuitous. Swire acquired the land at a discount of about 64 percent over its original asking price of $115 million.

“By building during the down cycle and starting early, they had pricing power that allowed them to achieve this scale,” real estate analyst Anthony Graziano said.

Through a succession of strategic purchases over a period of two years, the developer amassed sufficient real estate to cross a nine-acre threshold needed to qualify for special area planning, a designation that essentially allows large projects to function as special zoning districts. In lieu of building individual components as independent projects, special area planning “lets you be more creative in how you use your open-space requirements and density limits,” said Alice Bravo, director of transportation and public works for the city of Miami. The result, Katz said, is masterful execution of a grand vision.

Amenities

The first condo building, Reach, closed its first units in April. One-, two- and three-bedroom units — priced from $595,000 to $2.7 million— come with the services and facilities that have become standard for Miami condo residents: heated lap and social pools, concierge services, a Hammam spa with a nail salon and blow-out bar, children’s playroom, state-of-the-art gym, screening room, a library and a business center.

Because the project did not depend on outside financing, Swire did not begin sales until delivery of Reach was just about two years from completion. Without the 50 percent deposits required by financed developments, sales went directly to closing. Nearly 90 percent of the units at Reach were closed by late April, said Maile Aguila, Swire’s senior vice president of residential sales. Its twin, Rise, already more than 45 percent sold, is expected to be completed this summer, Aguila said. Most buyers hail from South America. About 70 percent of them are expected to be end-users. Part of the appeal for owners: a half- million square feet of entertainment just outside their door, due to open this fall.

“All you have to do is go downstairs to be a part of the action,” Aguila said.

That action includes an eclectic mix of retailers including Cole Haan, Valentino, Sephora, Chopard and Illesteva. Some were signed in cooperation with Whitman Family Development, owners of Bal Harbour Shops. Familiar culinary names include Pubbelly Sushi and Dr. Smood. At the center’s north end, a 38,000-square-foot Italian food hall will entice visitors with fresh produce and imported artisanal cheeses and meats. Live cooking demonstrations, classes by Italian chefs and wine tastings with food pairings will be scheduled regularly. Luxury movie theater Cinemex will open its first U.S. location here in the fall.

Integrated into the center’s third level is Metromover’s Eighth Street Station. Under a first-of-its kind arrangement with local government, Swire renovated the station and its surroundings — formerly a dumping ground. Under the 99-year agreement, Swire will manage and maintain the area, now transformed by gardens and home to a Saturday farmers market.

Over at EAST, Miami, Brickell City Centre’s 352-suite hotel, fine dining and drinking options abound, between the Argentinian rustic-meets-contemporary Quinto La Huella on the fifth level and Sugar, a rooftop bar set to offer an array of mixology libations and Asian-inspired tapas. The hotel is slated to open May 31, with a contemporary style laced with Asian influences carefully arranged by a feng shui master. Unlike most hotels, where top floors are reserved for high-priced suites, EAST, Miami features meeting spaces and restaurants on high floors, including a top-floor bathroom with killer city views.

“It’s going to be a total selfie moment,” Owens said. And while some play, others will work.

The lobby at Three Brickell City Centre at Brickell City centre, a 9.1-acre mixed-use project in downtown Miami. The tower’s anchor tenant is Akerman, a leading national law firm. (PHOTO CREDIT: CHARLES TRAINOR JR.)

A conference room at the law firm Akerman, the anchor tenant of Three Brickell City Centre at Brickell City Centre, a 9.1-acre mixed-use project in downtown Miami (PHOTO CREDIT: CHARLES TRAINOR JR.)

Law firm Akerman — which counts Swire as a client — is the anchor tenant of Three Brickell City Centre, one of the complex’s two Class-A office buildings.

“The decision to come here was because this afforded us a unique opportunity to work with a clean slate and in a complex that’s going to be the most exciting complex in downtown in decades,” said Neisen Kasdin, Akerman managing partner. “You feel like you’re in a major city like Hong Kong or Taipei, with the buildings connecting overground and underground, so there’s something exciting about that.”

Building High And Low

Engineering, and then building, the 9.1-acre city-within-a-city was no easy task. To ensure continuity across Brickell City Centre, Swire built underground parking garages topped by platforms that unite the project’s distinct structures. Underground parking is a rare, challenging and costly undertaking in downtown Miami, where elevation is low and soil conditions are tricky. Plus, the scale at which Swire is building — across five city blocks to accommodate 1,600 cars — was unprecedented.

“It was big, and it wasn’t proven,” said Chris Gandolfo, Swire Properties’ vice president of development.

A traditional garage in the complex interior would have been far cheaper — about $25,000 for standard indoor parking versus about $75,000 for the underground solution. But by sending cars beneath street level, Swire freed up lucrative retail space and reduced congestion with smoother, quicker traffic flows through the garages’ seven entrances and exits.

“It was a huge investment on their part and shows their commitment to the community by impacting traffic less,” said Bravo, the transportation director.

Engineers tested various construction methods to find the one that would be most cost effective, environmentally sustainable and safe in cases of emergency. Ultimately, Swire engineers modeled Brickell City Centre’s below-grade parking after PortMiami, where the underground tunnel was built using “deep soil mixing,” a method that involves drilling more than 30 feet into the ground and mixing soil into a concrete texture.

A rendering of the entertainment and retail center at Brickell City Centre, a 9.1-acre mixed-use project in downtown Miami (PHOTO CREDIT: SWIRE PROPERTIES)

Above ground, Swire built platforms over the street level that link shops, restaurants, hotel and the other buildings. Within the shopping center, bridges sustain connectivity throughout the half-a-million-square-foot space. Creating hurricane-proof above-grade pedestrian crossings that also could withstand the weight of the 150,000-square-foot-long climate ribbon also required an engineering feat. Swire’s team merged structural steel into a concrete design that weighs about 1,200 tons.

“We had numerous city blocks but the only way Brickell City Centre would work is with connectivity, so with the bridges, you have a continuous experience,” Owens said.

Additionally, loading docks were integrated into the mega development’s various towers, a decision Bravo lauds unabashedly.

“That is a huge, huge convenience because that’s a big, big problem we have in downtown in Miami and other parts of the county, where loading trucks are causing all kinds of traffic disruptions.”

Inland Properties With Waterfront Values

As Brickell City Centre continues to flourish, adjacent developments are reaping fringe benefits. Vanessa Grout, president of CMC Group’s real estate marketing and sales division, said the promise of world-class dining and shopping afforded by Brickell City Centre has lured countless buyers to CMC’s newest luxury condo tower, Brickell Flatiron. Brochures of the development include a guide to the Brickell area that prominently features City Centre as a neighborhood amenity, Grout said.

“There’s a lot of excitement and enthusiasm because everyone knows that as soon as Brickell City Centre opens, it will provide a lot of entertainment and a great retail experience,” Grout said. “You can really say that Brickell City Centre has created a more vibrant community, while carrying value of property further west and away from the water.”

On the tax basis alone, City Centre “will be a huge infusion of value to the urban core,” the DDA’s Robertson said.

Real estate analyst Graziano said large-scale, high-quality developments tend to increase property values, particularly when acting as an infill development that elevates the pedestrian experience. “ Properties surrounding it are definitely riding its coattails,” Graziano said.

As for the culinary scene, “Despite Miami’s immense cultural growth and its rich culinary scene, we have yet to see a food concept quite as extensive as the food hall being introduced at Brickell City Centre,” said Debora Overholt, vice president at Swire Properties. “Miami is a thriving international city and is ready for this magnitude of culinary experience.”

City Centre has also filled a gap in the retail landscape, according to experts. Anchored by a Saks Fifth Avenue, the shops will “fill in a retail-sized hole in the doughnut of downtown Miami,” Robertson said.

Current downtown shopping options are limited, often more oriented to tourists than residents. North of the Miami River sits Bayside Marketplace, “but a lot of locals don’t think of going to Bayside,” where the biggest brand names are Skechers and Victoria’s Secret, said Cynthia Cohen, president of Miami-based retail and real estate consulting firm Strategic Mindshare.

Mary Brickell Village is hardly on shoppers’ radar either, according to Cohen, because of its weak tenant mix — an all-important factor that determines a retail center’s success. Residents of downtown Miami are left to trek to Merrick Park, Aventura Mall or Dadeland Mall for retail therapy.

“The issue really is, shopping on a map doesn’t look that far away in terms of mileage, but in terms of time and the heavy, heavy traffic in the Brickell corridor and U.S. 1, the time required to get to the other shopping destinations is prohibitive,” and decreases the frequency with which people shop — and eat, “a big part of shopping,” Cohen said.

Closer are Midtown Miami, whose sole department store is Target, and the ultra-luxury shops of the Design District. Plans for Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s department stores at Miami Worldcenter have been sidelined. Developers of the 27-acre complex announced in January that they would opt for an open-air design, instead of a traditional mall layout, which may potentially be incapable of accommodating larger “big box” locations. The food and entertainment offerings may even keep neighborhood residents from heading elsewhere — thus cutting down on traffic.

“High-rise development in high-density areas … can be the best thing for the community if they look at the big picture,” said Allen W. Morris, a developer not involved with the project. Development in the urban core “is actually the green alternative.”

Green Engineering

The underside of the climate ribbon, a climate control sculpture at Brickell City Centre, a 9.1-acre mixed-use project in downtown Miami (PHOTO CREDIT: CHARLES TRAINOR JR.)

Brickell City Centre’s developers say that throughout the design process, sustainability was front of mind. The $30 million “climate ribbon” over the shopping center’s open concourses, for instance, is more than a shade against sun and rain.

“We always knew we needed to have some kind of cover for pedestrian shoppers, but we realized soon in the development of the climate ribbon [that] it could be a lot more,” said Gandolfo, vice president of development for Swire.

The 150,000-square-foot canopy of insulating glass and steel also store rainwater that is reused to irrigate City Centre’s green rooftops. The first-of-its-kind climate ribbon was created through a collaboration between a Paris design firm and the universities of Carnegie-Mellon in Pittsburgh and Cardiff in the United Kingdom.

“It’s a solution to climate management that turned out to be wonderfully artistic,” Owens said. Without the undulating structure, the open-air space would instead feel like just another mall, “and that could be in Denver or Dallas. But we wanted it to feel like Miami.”

Swire also relocated 50 200-year-old oak, gumbo limbo and strangler fig trees from the property.

It was no simple task. The trees, which weigh between 35,000 and 128,000 pounds each, were transported over four city blocks and up the Miami River to Museum Park, where Buddhist monks from Tibet blessed them in a ceremony that took place April 22, Earth Day. Some of the more delicate trees were repurposed and gifted to local artists; others were sent to Jungle Island to be incorporated into cat and bird habitats. A horticulturalist estimated that about 10 of the 50 trees wouldn’t make it, Owens said. All survived.

In It For The Long Haul

Swire’s Eastern roots are apparent in more than the Buddhist ceremony and the hotel’s feng shui. Unlike U.S. companies focused on quarterly returns, Swire takes a long view.

“Asian companies do not look at short-term returns. I would almost call them generational investors,” said real estate analyst Jack McCabe, “in that before they invest, they do years of research, much longer than we do in the U.S. But once they make the determination that they’re going to invest in something, they’re looking at years and years of investment.”

While most U.S. developers divest of management contracts once construction is complete, Swire retains management of its condos as well as ownership and management of commercial space.

Case in point: In the 1980s, Swire purchased Claughton Island as raw land. More than two decades after developing it as Brickell Key, Swire still manages its condo associations and office buildings. Mandarin Oriental, a member of the Hong Kong-based Matheson Jardine group, runs the hotel.

With Brickell City Centre, Swire demonstrated not just commitment, but foresight, analysts say.

“Anything done in ’08, ’09 and ’10 was a risk. Nobody could tell me they saw through the clouds,” said the Aztec Group’s Katz. “It takes a real visionary to think about a project of that magnitude and act upon it, and they really are long-term thinkers.”

City Centre Timeline

- November 2008: Swire purchases 5.65 acres for $41 million.

- July 2012: Swire purchases 3.24 acres for $27 million.

- June 2011: City of Miami approves plans for 9.1-acre Brickell City Centre.

- June 2012: Brickell City Centre breaks ground.

- February 2016: Brickell City Centre opens first building, office tower Three Brickell City Centre.

- May 2016: EAST, Miami hotel will debut.

- June 2016: Second office tower, Two Brickell City Centre, will be completed.

- Summer 2016: Condo tower Rise expected to open.

- Fall 2016: Retail and entertainment center slated to open.

City Centre Snapshot

Cost: $1.05 billion.

Size: 5.4 million square feet/9.1 acres.

Local jobs created: 2,500 during construction phase; 3,700 direct jobs and 2,500 indirect jobs created after completion.

Elements

- Two mid-rise office buildings.

- Two residential towers, Reach and Rise, 390 units each.

- EAST, Miami hotel, with 352 rooms, including 89 fully serviced residences.

- Retail and entertainment center, anchored by Saks Fifth Avenue and comprising 125 tenants, spanning 500,000 square feet.

Swire Group

Publicly traded and wholly owned conglomerate with operations in trade, property and aviation. Miami’s Swire Properties is a wholly owned subsidiary.

- Founded: 1816 in Liverpool, UK, as John Swire & Sons.

- Based: In London and Hong Kong (Swire Pacific Ltd.).

- Employees: 129,793.

- Swire Properties Inc.: U.S. real estate subsidiary, headquartered in Miami since 1979.

- Swire Properties Miami leadership: Stephen Owens, president; Christopher Gandolfo, senior vice president of development; Maile Aguila, senior vice president, director of sales.

- Major mixed-use developments: Taikoo Place & City Plaza, Hong Kong (9 million square feet); Pacific Place, Hong Kong (5.19 million square feet); INDIGO, Beijing (1.89 million square feet).

- Total real estate developments worldwide:48.

- Other corporate holdings: Cathay Pacific (Hong Kong’s largest airline); Coca-Cola bottling (Hong Kong, mainland China, Taiwan); Haeco (aircraft engineering, based in Hong Kong) .

Brickell Key

Swire began to develop the 44-acre Brickell Key island in the 1980s, beginning with Brickell Key One, which was completed in 1982.

-

- Brickell Key development cost: $1 billion.

- Residential projects: Asia (123 units); Carbonell (284 units); Jade Residences (338); One, Two and Three Tequesta Point (288 units; 268 units; 236 units); Courts Brickell Key (319 units); Courvoisier Courts (272 units); Brickell Key One (301 units).

- Commercial projects: Mandarin Oriental hotel (328 rooms and suites); Courvoisier Centre twin-tower office complex (315,000 square feet); Brickell Key Marketplace.

Source: Miami Herald

A European artisanal food market has secured a three-story, 38,000-square-foot space within Brickell City Centre‘s 500,000-square-foot shopping center, developers of the soon-to-open project announced this week.

Swire Properties, along with retail co-developers Whitman Family Development and Simon Property Group said the indoor Italian food hall will anchor the $1.05 billion project’s open-air shopping center being built in Miami’s Brickell financial district.

“We want to bring the tradition and energy of the old world Italian streets and town centers, or piazza, to Miami’s urban core, creating a vibrant central destination for the Brickell community and beyond,” said the companies in a joint statement. “A food market is the heart and soul of most major Italian cities; now the same will be true here in Miami.”

The food market will open within the north block of the shopping center and feature a variety of eateries selling Italian cuisine. Their wares will include produce, home-meal replacements and imported artisanal cheeses and meats. There will also be live cooking demonstrations, classes by Italian chefs and educational programs on wine and food pairing at the food hall.

“Despite Miami’s immense cultural growth and its rich culinary scene, we have yet to see a food concept quite as extensive as what our food hall partners are introducing at Brickell City Centre,” said Debora Overholt, vice president at Swire Properties, in a statement.

Other restaurants Brickell City Centre has confirmed to open in its shopping center include Pubbelly Sushi, Haagen Dazs, Pasion del Cielo, Taco Chic, American Harvest and others. More food options are available at Brickell City Centre on Sundays, when its weekly, year-round farmers market takes place along the landscaped pathway that runs between Seventh Street and Eighth Street, directly underneath the Metromover track. Its first event was last weekend.

Brickell City Centre encompasses 5.4 million square feet of commercial, residential, office and hotel space, slated to open later this year. In addition to its 500,000-square-foot shopping center, the project includes two condo towers, the 352-room East, Miami hotel and several office buildings.

Source: SFBJ

The developer of Brickell City Centre has placed a larger bet on the office market, as it has converted a planned wellness usage into “Class A” office.

In 2014, law firm Akerman LLP signed a lease to occupy 80 percent of the 130,000-square-foot Brickell City Centre Green tower that was under construction as part of the $1.05 billion project in Miami. The rest of the space was supposed to be for wellness, but developer Swire Properties has made the 26,000 square feet available for office tenants. It also rebranded the tower Three Brickell City Centre. The project will include another office tower of the same size, Two Brickell City Centre.

“One of the two towers, Three Brickell City Centre, although designed with use flexibility, was originally designated as a wellness center, but current market conditions show demand for additional office space,” said Edward Owen, Swire Properties’ office leasing manager. “Swire decided that it was in the best interest of the market to create supply to further Brickell’s growth as a leading international business hub.”

Arquitectonica designed both buildings, which will have floor-to-ceiling glass and 10-foot high walls. Brickell City Centre will also feature a shopping center, restaurants, condos and a hotel. The office, condo and hotel parts of the project should be ready this winter.

According to Cushman & Wakefield’s second quarter report, the Class A office market in downtown Miami has a 13.3 percent vacancy rate and average asking rent of $41.81 per square foot. The last new office delivery was 2010.

CBRE reports that about 1 million square feet of office space is under construction in Miami-Dade County, with Brickell City Centre and All Aboard Florida’s Miami Central Station as the largest projects.

The Business Journal is tracking another 5.4 million square feet of office space that’s in the pipeline in South Florida, as described in a recent centerpiece.

Click here for a “Behind the Scenes” slideshow of the Brickell City Center

Source: SFBJ

About Us

Ven-American Real Estate, Inc. established in 1991, is a full service commercial and residential real estate firm offering brokerage and property management services.

Subscribe

Contact Us

Ven-American Real Estate, Inc.

2401 SW 145th Avenue, Ste 407

Miramar, FL 33027

Brokerage & Property Management Services

Phone: 305-858-1188